The Living Abstraction of Gothic Art the Vampire Film Undead Cinema

Abstract

Horror flick scholarship has generally suggested that the supernatural vampire either did not appear onscreen during the early on movie theatre menstruum, or that information technology appeared simply once, in Georges Méliès' Le manoir du diable/The Devil'south Castle (1896). By making rigorous utilise of archival materials, this essay tests those assumptions and determines them to exist wrong, while at the same fourth dimension acknowledging the ambiguity of vampires and early cinema, both existence decumbent to misreadings and misunderstandings. Between 1895 and 1915, moving pictures underwent major evolutions that transformed their narrative codes of intelligibility. During the same years, the bailiwick of vampirism also experienced great modify, with the supernatural characters of sociology largely dislocated by the not-supernatural "vamps" of popular culture. In an effort to reconcile the onscreen ambiguities, this paper adopts a New Film History methodology to examine four early films distributed in America, showing how characters in two of them—Le manoir du diable and La légende du fantôme/Legend of a Ghost (Pathé Frères, 1908) have in dissimilar eras been mistakenly read as supernatural vampires, too as how a third—The Vampire, a little-known chapter of the serial The Exploits of Elaine (Pathé, 1915)—invoked supernatural vampirism, but simply as a metaphor. The paper concludes by analyzing Loïe Fuller (Pathé Frères, 1905), the only picture of the era that seems to have depicted a supernatural vampire. Revising the early history of vampires onscreen brings renewed focus to the intrinsic similarities between the supernatural creatures and the movie house.

Introdution

In Bram Stoker'due south Dracula (1992), Francis Ford Coppola depicts Count Dracula (Gary Oldman) walking through London in grainy footage that appears to take been shot at xvi or 18 frames per 2d. The sound of a moving-picture show projector tin be heard in the background, as can a street barker inviting passersby to "see the astonishing Cinématographe." Dracula and Mina (Winona Ryder) nourish the operation, with the moving pictures arousing the vampire's bloodlust. On two occasions, a stark and phantom-like train appears onscreen behind the Count; Coppola created these images for his moving-picture show, inspired by such films as L'arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat/Arrival of a Train at the Station (Lumière, 1895) and The Ghost Train (American Mutoscope and Biograph, 1901) (Cordell, 2013, p 1). Here Coppola links vampirism and the cinema, in part because Stoker's novel was published in 1897, at roughly the same time that public film projections became common.

But there is potentially another, deeper link between the cinema and the supernatural. "Last night I was in the Kingdom of Shadows," Saying Gorky famously recounted after visiting a Lumière film screening in July 1896. "If you just knew how strange it is to exist at that place," he wrote:

It is not life, but life'south shadow, it is not motion, only its soundless spectre…. It is terrifying to see, but it is the motion of shadows, only of shadows. Curses and ghosts, the evil spirits that have cast entire cities into eternal sleep, come up to mind… (Harding, p 5).

Gorky was not alone in likening moving pictures to the supernatural. Woodville Latham and his sons might well have considered that metaphor while inventing their "Eidoloscope," which Musser (1990a) has called "the start American motorcar for projecting motion pictures" (p 91). Their projector fabricated its public debut in April 1895. It was named after the "eidolon" of Greek literature, significant a phantom, spectre, or spirit-prototype of a person. Less than vi months subsequently, in September 1895, C. Francis Jenkins and Thomas Armat premiered their own invention, America's first commercially viable projector using an intermittent mechanism. They called it the Phantoscope (Musser, 1990a, p 103). On Oct iii, 1895, the Baltimore Dominicus chosen it "mysterious" (p 2).

Perceived connections betwixt vampirism and early and silent movie house continue to resonate. E. Elias Merhige's Shadow of the Vampire (2000), a fantastical account of the making of Nosferatu (1922), features Willem Dafoe as actor Max Schreck. In this alternate history, Schreck is an actual vampire, hired by managing director F. W. Murnau (John Malkovich) to add together realism to his motion film. In i scene, Schreck becomes fascinated by a flick projector, peering into its lens, the light flickering on his face. He has become projected. Merhige constructs a powerful metaphor, one that bears relation to Coppola's.

1 demand just consider the question of where movie theatre resides to understand the authority of these vampiric metaphors. Motion-picture show is spooled effectually a reel, but that is not where audience sees it. Rather, calorie-free passes through frames separated by black infinite, pulsing temporally and temporarily on a screen. Simply fifty-fifty the screen is not a flick'southward permanent dwelling house, certainly non in the same mode that a frame provides to a painting. The location of a motion picture is in flux. A motion picture is most alive while it is existence projected, materialized in the darkness, simultaneously luminous and tenebrous, and that is when it exists between ii worlds. Much the same is truthful of a vampire, its status is hard to locate, let alone comprehend. To be undead is to be neither alive nor expressionless, but rather to be in a strange twilight amidst the two, unreal and corporeal at the same time.

To these longstanding comparisons, another should be considered, the notion that—for a variety of reasons during the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth—the cinema and vampirism both underwent various evolutions that impacted heavily on the ability of audiences to comprehend them, to make sense of them. The two regularly pose questions, just those questions are particularly pronounced when because the period from 1895 to 1915. To explore this issue, the United States serves equally an important case study, as information technology represents a geographical location in which these bug at times collide and at times converge. The protean vampire was never more instable than in America during those years.

Here the question is whether or non the undead walked onscreen in early cinema. Consider Stacey Abbott's monograph Celluloid Vampires: Life later on Death in the Modernistic World (2007), in which she writes the "vampire was absent from the early on days of movie house" (p 44), subsequently having already announced, "French magician and filmmaker Georges Méliès brought forth the start celluloid vampire in his [1896] film Le manoir du diable" (one), but prior to describing the character in that same film every bit a "satanic figure" (p 50). It is non the apparent contradiction in these comments that is important, just instead the reasons for the defoliation that exist in the annal and in the scholarship.

Nowhere are these issues more pronounced than in four moving pictures produced between 1896 and 1915, all of them screened in the United States: Le manoir du diable/The Devil's Castle (Georges Méliès, 1896), which modern critics accept sometimes mistaken as a supernatural vampire film; La légende du fantôme/Fable of a Ghost (Pathé Frères, 1908, aka The Blackness Pearl), which one American critic in 1908 mistook equally featuring a supernatural vampire; The Vampire, episode six of the serial The Exploits of Elaine (Pathé, 1915), which invoked supernatural vampirism, simply only to deploy it as a metaphor; and Loïe Fuller (Pathé Frères, 1905), which featured what might well have been intended to be a supernatural vampire.

These case studies let consideration of what the primeval vampire films were, or at least might have been, an of import pursuit given scholarly interest in early cinema and horror studies. It is every bit easy to exist equally excited past the vampire in early picture palace every bit Coppola was. All the same, these four films besides allow u.s. to explore the paradoxical nature of vampires and early on cinema. At times, both are murky, their images fleeting and indistinct, their stories needing to be read, just always at the run a risk of beingness misread.

Ambiguity

In addition to her comments on the vampire in early movie house, Abbott informs readers that Nosferatu (Murnau, 1922) represented the "cinema's first entirely cinematic vampire, drawing upon the ambiguity between the living and the dead, the scientific and the fantastic" (p 44–45). Her argument has much merit, founded every bit it is upon the types of ambiguities that Coppola earlier explored in Bram Stoker'due south Dracula and that should be observed when examining vampirism and early cinema. Consider the following account from Rhode Island, published in the Tacoma News on March 28, 1896, only days before Edison'due south Vitascope premiered at Koster and Bial's in New York City:

It gives one a creeping awareness of horror to recall that in enlightened New England, during the final decade of the nineteenth century, the corpse of a young woman buried eight weeks was dug out of the basis, the eye and liver cut out and burned, and all this that the dead might cease to be nourished at the expense of living relatives (p 3).

In this example, the understanding of and belief in supernatural vampires was then strong that a suspected corpse was exhumed. The incident stemmed from established and readily understood superstitions. As early as June 15, 1732, the American Weekly Mercury published a non-fiction account almost Hungary that claimed "certain Dead Bodies (called here Vampyres) killed several persons by sucking out all their blood" (p 2). During the nineteenth century, Americans learned near vampires from the increasing office that such they played in fictional literature and entertainment, including in the notable cases of John Polidori'due south 1819 curt story The Vampyre, A Tale and James Robinson Planché's 1820 play The Vampyre; or, The Bride of the Isles (aka The Vampire, or the Bride of the Isles), which was staged repeatedly in the decades after its premiere.

Yet, in 1897, Philip Burne-Jones'southward painting The Vampire, and Rudyard Kipling'south companion poem of the same name, recast the supernatural creature as a mortal woman who metaphorically bleeds men of their lives. The effect on popular culture was so robust that many persons were no longer certain as to what a vampire was. For some, the term became plural, indicative of old superstitions and contempo art. For others, the new definition dispossessed the old, despite the success of Bram Stoker's novel Dracula (1897), beginning published in America in 1899.

The impact of the Burne-Jones painting and Kipling'southward poem on American usage of the term "vampire" had an immediate and profound upshot. On March 5, 1899, a journalist in the New York Times reported:

People nowadays carelessly use the discussion 'vampire' as a stronger and trifle more loathsome term than 'parasite.' Burne-Jones once painted a picture called the Vampire. Information technology was a very beautiful adult female leaning over a man she had only slain. And Kipling wrote some symbolic verses about it (IMS2).

The journalist added his view that "Probably few persons know what the real vampire is," the Burne-Jones depiction having so quickly displaced the supernatural character in much of popular culture.

Indeed, despite the success of Stoker's novel, the foremost understanding of vampirism in America in the early twentieth century remained the Burne-Jones and Kipling grapheme. Consider this article published in the Chicago Tribune article in January 25, 1903:

'What is a vampire, anyway?' asked a young woman looking at the Burne-Jones motion-picture show at present on exhibition.

'A vampire,' [replied] her companion. 'A vampire is the rag and a bone and a hank of hair that Kipling talks nearly.'

They probably had non spent a portion of their youthful lives in a small boondocks visited occasionally past the 'greatest show on earth' with its sideshow. If they had they would have known all most the 'blood sucking vampire.' They would have dreamed almost it… (p forty).

Exasperated by cultural confusion over the term, the journalist felt compelled to describe supernatural vampires in great detail, both in their folkloric roots and in Stoker'southward novel, all in an effort to (re-) educate at least some Americans.

Nevertheless, the Burne-Jones vampire connected to boss American pop culture thanks in big measure to Porter Emerson Browne'due south 1909 novel A Fool In that location Was, which he quickly adjusted for the stage. In 1910, Selig Polyscope produced the moving picture The Vampire, which attempted to bring the Burne-Jones painting to life and even quoted Kipling in its intertitles. A large number of "vamp" films followed, with A Fool There Was (Fob, 1915) starring Theda Bara existence the about famous. Not surprisingly, when David McKay published the commencement American edition of Dudley Wright'due south book Vampires and Vampirism in 1914, it was necessary to begin with the question: "What is a vampire?" (Wright, 2001, p 1).

Questions of pregnant and legibility are also crucial in the viewing of early cinema, its flick content striking some later viewers equally so singled-out from the Classical Hollywood Style equally to advise an avant-garde. For example, the Bruce Posner-curated DVD collection Unseen Picture palace: Early American Advanced Film, 1894–1941 features many moving pictures produced earlier 1915, including by such mainstream companies every bit the Edison Manufacturing Company and American Mutoscope & Biograph. Kristin Thompson (1995) has argued that information technology is "only after the formulation of classical Hollywood norms was well advanced that nosotros can speak of an avant-garde alternative" (p 68). But whether one views a term similar "avant-garde" to be a modern imposition on early cinema or whether one concentrates on—equally Bart Testa (1992) sees it—the "back and forth" interactions between early on cinema and later avant-garde films that appropriated footage from the menstruation, the give-and-take must consider that some early film narratives are opaque, if non obscure. Their "codes of intelligibility," as Thomas Elsaesser (1990b, p 11) calls them, can pose challenges for mod audiences, only equally they did for some of their original viewers.

Tom Gunning, André Gaudreault, Charles Musser, and others who have analyzed early cinema narratives accept accordingly complicated the period, observing different and evolving narrative patterns. Gunning (1990a) believes the earliest films represented a "cinema of attractions," meaning not only that motion-picture show exhibitions were themselves attractions (including in terms of the sit-in of project equipment), just as well that, during its early years, the cinema tended to focus on the presentational and the spectacular in order to incite "visual curiosity" and supply visual "pleasure" (p 56). As Gunning (1990b) writes, "this cinema differs from later on narrative cinema through its fascination in the thrill of display rather than its construction of a story" (p 100). Narrative storylines were minimal, and so the possibility for them to be misread was very real.

Gunning (1990a) originally suggested that the menstruation from 1907 to approximately 1911 "represents the truthful narrativization of the cinema" (p 60). In his later work (1993), he augmented that view past noting the cinema of attractions predominated until circa 1903, followed past a flow of transition that lasted until circa 1908 (p 10–xi). At no other menstruum during the history of American film did greater alter occur, unfolding, as Elsaesser (1990a) has observed, not every bit a linear progression, only in "in leaps; not on a single front, merely in more jagged lines and waves: this history of film grade emerges every bit a complicated transformational process involving shifts in several dimensions" (p 408).

Every bit the early cinema period progressed, film narratives became simultaneously more complicated and more legible. For example, Gunning's 1991 monograph on D.Westward. Griffith includes a chapter entitled "Complete and Coherent Films, Cocky-Independent Commodities," which argues the "narrator system … came into focus" by the end of 1908 (p 130). That said, audiences still experienced occasional difficulty in comprehending given film narratives. On Jan 7, 1911, a journalist for the Moving Flick World remarked:

Ambiguity in pictures is one of the chief failures of the day in moving movie subjects; this is axiomatic to the critic and the public. If merely the critic experienced this ambiguity, it might become a matter of opinion between great minds, but when the educatee of moving pictures finds it difficult sufficiently to grasp the 'plot' or see the 'signal,' at that place is further evidence of this weakness … the public is total of inquiries then that when sitting in the theaters 1 overhears a constant stream of queries—specially the exclamation at the sudden abrupt or ambiguous catastrophe of a subject (p fourteen).

The same journalist also recounted such "audible exclamations" from viewers as "What does it mean?" and "Could y'all understand it?" (p 40).

For Gunning (1990b), early cinema represents a "paradox" in that it is "simultaneously different from later on practices—an alternate movie theatre—and yet profoundly related to the cinema that followed information technology" (p 102). It is an evolving cinema, and its relationship to later film practices might well be one of the reasons it can be difficult to view intelligibly. Anyone in the twenty-commencement century struggles to avert seeing these moving pictures through the lens of post-1915 filmmaking. It is on occasion challenging fifty-fifty for film theorists and historians to read given films from the early cinema period with precision.

The penumbra of vampires that appeared during the years from approximately 1897 to 1915 besides represent a paradox, one in which distinctive characters emerge in jagged lines and waves, some supernatural and some not, all equally part of a circuitous transformational process in which—despite their differences—alternate vampires spawned by Burne-Jones and Kipling were profoundly related to those that came earlier and which would appear afterwards. The result was a complicated and overlapping prepare of vampire depictions that are besides difficult to read, to analyze, to fathom. As Browning and Picart (2009) have observed, "The vampire is a construction that is nether continuous evolution, an assemblage of words, images, and places especially that well-nigh resembles a Frankensteinian creature" (p 17). It is into this Kingdom of Shadows that scholars must venture.

Le manoir du diable/The Devil's Castle (1896)

Georges Méliès' Le manoir du diable (1896) is a fundamental example of the horror-themed film in early on cinema. Its tone is more serious than many of his subsequent films, which generally focussed on humor, and its visual content presents a number of tropes afterward associated with the horror film genre, among them devils, ghosts, and witches inside a haunted castle. Believed lost for decades, a copy resurfaced in 1988 at the Ngā Taonga Audio & Vision archive, appearing on the Flicker Alley DVD Georges Méliès Encore in 2010.

In America, Lubin distributed Le manoir du diable as The Devil's Castle; Edison released information technology every bit The Infernal Palace (Edison Films, No. 94, 1900, p 39–40). When American audiences first saw it is difficult to determine. The film appears in American Vitagraph'southward 1900 List of New Films, which offered information technology in three lengths, significant 50, 100, or 200 feet (p two). However, newspaper advertisements every bit early as 1899 listing Lubin's title being screened at moving picture exhibits. For instance, on Apr ii, 1899, an advertisement in the New York Times for Huber's Museum publicized the "Historiograph" on a bill with live entertainment fabricated up of: "Regal Japanese Wrestlers and Acrobats, Great Success of Allini'southward Monkeys, Boxing Bouts, Wire Walking, and Trapeze Performance" (p 17). The Historiograph was to nowadays 25 minutes of moving pictures, but The Devil'south Castle—which the advertizement promised would exist screened "complete in every detail" (p 17)—was the only 1 that was named.

Later that same month, the Ninth and Arch Museum in Philadelphia featured a vaudeville show that ended with the "Cineograph" moving pictures. Foremost amidst the group were two Méliès films, L'homme dans la lune/A Trip to the Moon (1899, aka Astronomer's Dream) and The Devil's Castle. An advertising published in the Philadelphia Inquirer on April 30, 1899 touted the duo equally "the near striking moving pictures ever taken" (p 12). In yet some other indication of its apparent popularity, an article on film piracy printed in the Davenport Weekly Leader on June 7, 1901 specifically cited The Devil'due south Castle equally one of six Méliès films that had been illegally duped. The culprits included Lubin, who continued to sell the film in his catalogs until equally late equally 1908 (Lubin'south Films, 1908, p S6).

Along with Stacey Abbott, numerous writers in the modernistic era have referred to The Devil's Castle as—to employ the words of J. Gordon Melton (2011)—the "very kickoff vampire film" (p 448). Such a judgment appears in monographs, academic papers, and vampire-related websites. Footnote 1 Nowhere is this more evident than in the title of John L. Flynn's 1992 book Cinematic Vampires: The Living Expressionless on Film and Tv set, from The Devil'southward Castle (1896) to Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992). Only however crucial Méliès' moving moving picture was, with all the many horror conventions information technology introduced to cinema, no vampires appear during its running time. There are ghosts and witches, a devil and an imp, only no vampires. None whatsoever.

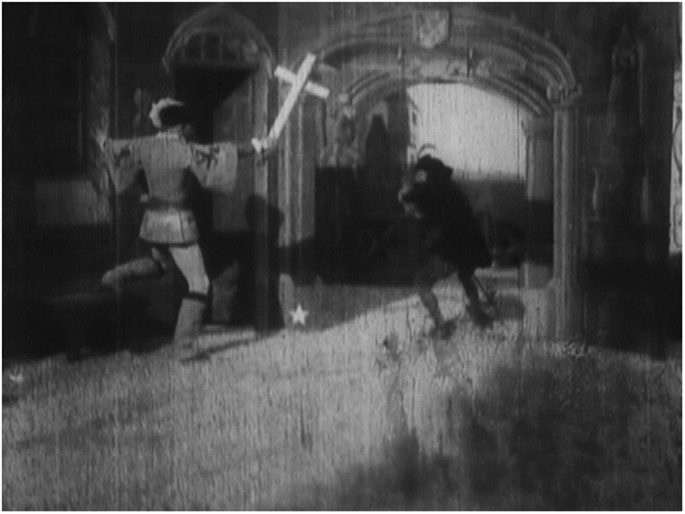

To brainstorm, the picture's original title and most mutual English translation indicate that the key villain depicted is a devil, non a vampire. Footnote 2 Méliès reiterates this point in the character's appearance: the devil's costume features pronounced material horns, much equally stage productions of Faust had done throughout the nineteenth century. Film catalogs reinforce this interpretation. In 1900, Edison Films, No. 94 described its climax as follows: "Finally 1 of the cavaliers produces a cross, and Mephistopheles throws up his easily and disappears in a cloud of smoke" (p 40; encounter Fig. ane). Then, in January 1903, the Consummate Catalogue of Lubin'southward Films said much the aforementioned: "Satan… vanishes immediately when the Cross [sic] is held before him" (p 20).

During the era of sound picture palace, the use of a cantankerous to dispel vampires became and then common equally to obscure the fact that the same religious iconography had been used in an before age to dispel devils. Consider the short story A Ghost, published in the Connecticut Gazette on Baronial 30, 1797, in which the narrator tells u.s.a.: "At length I ended, if it be a demon, he will fly at the sign of the cross" (p one). This was also true, for example, in the ballet Uriella, the Demon of the Dark, which was staged in New York in 1870. It was besides true in early cinema. In Le fils du diable/Mephisto's Son (Pathé Frères, 1906), the son of Satan cowers before a priest conveying a cross. On October three, 1908, Moving Movie Globe told readers that, in Vitagraph's The Gambler and the Devil (1908), the female lead "holds upwards a cross earlier him. The devil covers his optics with his hands, there is a puff of smoke, and he disappears" (p 267). And so, on March xviii, 1911, the same publication wrote that, in La défaite de Satan/Satan Defeated (Pathé Frères, 1910), a grapheme "holds upwardly the crucifix and Satan disappears forever" (p 602).

If the use of the cross is ane reason that modern viewers have mistaken the devil character for being a vampire, the other is moving-picture show'south opening, in which a large bat transforms into Mephistopheles (Fig. ii). Here over again, the emphasis in vampire literature and films of the mail service-1896 era accept clouded the ability for modern viewers to read The Devil's Castle as it was intended. Indeed, even though he acknowledges the character is Mephistopheles and not a vampire, Stephen Prince (2004) notwithstanding refers to the prop every bit a "vampire bat" (p 1), when there is no historical or textual reason to suggest the bat is or was specifically meant to be a vampire bat.

Satan is not a vampire, only prior to 1896 there is a lengthy history that gives him demonic wings or even likens him to a bat. Information technology is of import to recall Ephesians 2:two, which describes Satan equally the "prince of the power of the air." To enumerate the sheer volume of artwork over the centuries that depicts devils and demons as having bat-like wings and talons would exist difficult. Famous examples include Botticelli'southward and Doré'south illustrations for Dante's Inferno, as well every bit Doré'southward engravings for Milton's Paradise Lost. The same is true in tardily nineteenth-century visual civilisation, including in many French "diablerie" stereographs (Borton and Borton, 2014, p 139).

A frame from Georges Méliès' Le manoir du diable (1896). A crucifix is used to dispel the moving-picture show's devil. As this work was published earlier 1923, it is in the public domain. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

A frame from Georges Méliès' Le manoir du diable (1896). The devil appears in the grade of a bat. As this work was published before 1923, information technology is in the public domain. This figure is covered past the Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Here again the same can be identified repeatedly in early on cinema, including in Méliès' Le diable au couvent/The Devil in the Convent (Méliès, 1900, aka The Sign of the Cross; or the Devil in a Convent), in which Satan flies into the convent, and in Méliès' Le Chevalier des Neiges/The Knight of the Snowfall (1912), in which a bat keepsake appears on the devil's shirt, as well as on a large banner behind him. But the imagery was hardly unique to Méliès. An advertizing for the Italian-fabricated Satana, ovvero il dramma dell'umanità/Satan, or, The Drama of Humanity (Ambrosio, 1912) published on January 11, 1913 in the Moving Picture Globe used artwork of a bat to promote a pic about the devil's negative touch on humankind. No narrative or visual cues in these cases suggest such wings or bats take any affiliation with vampirism or, for that matter, that the bats depicted are specificallyvampire bats.

Given that The Devil's Castle was hardly unique in its treatment of Satan, the picture'south meaning was probably unambiguous to original audiences. But that has not proven true of modern viewers, who take imposed their awareness of after Hollywood vampire movie house onto Méliès, seeing a vampire where one did non exist. A key manner to understand and correct this fault is to consider Charles Musser'south enquiry on Edwin S. Porter'south The Great Train Robbery (Edison, 1903), a film regularly cited as the first, or one of the first, westerns. Perceiving this to exist a "retrospective reading," one that positions the film within a film genre that did not yet exist, Musser examines The Great Train Robbery in relation to moving pictures that preceded it, specifically in "its ability to comprise so many trends, genres and strategies fundamental to the institution of cinema at the fourth dimension" (1990b, p 130). Footnote 3 These included the travel genre (specifically the railway subgenre), the genre of re-enacted news events, and the crime genre. Footnote iv The Devil's Castle as well integrated characters and narrative concerns that preceded it, none of them involving supernatural vampires.

La légende du fantôme/Fable of a Ghost (1908)

If one person became Georges Méliès' immediate heir, it was Segundo de Chomón, a Spanish filmmaker whose expertise with coloring moving pictures gained him piece of work at Pathé Frères in 1905. He became "one of the chief supervisors (and shortly later on, the manager) of the company's pull a fast one on film section" (Batllori, 2009, p 97). In many means, his narrative and artful approach intentionally mimicked Méliès; in 1908, for example, he remade Méliès' Le Voyage dans la lune/A Trip to the Moon (1902) as Excursion dans la lune/An Excursion to the Moon (Pathé Frères, aka Excursion to Moon). Footnote 5 But in other respects, Chomón advanced the trick motion-picture show, including in his adept use of color and animation.

Of particular importance is the fact that Chomón at times used tricks to construct dramatic, horror-themed storylines, nearly notably in the hand-colored La légende du fantôme/Legend of a Ghost (Pathé Frères, 1908). Footnote 6 Here is a key link in the development of the horror-themed movie, with the attraction of cinematic tricks logically embedded into a dramatic narrative, ane inspired past Dante'southward Inferno and the Greek myth of Orpheus. How American audiences reacted at the time is hard to determine, but on May 23, 1908, Variety praised the film's "curious, mystic light effects," which were "well handled to raise the weirdness of the scenes" (p 12).

For at to the lowest degree i person in 1908, Fable of a Ghost depicted a supernatural vampire. According to a plot synopsis published in Moving Picture Globe on May 23, 1908:

Arriving at the gate of Satan's kingdom, they mount a chariot of burn down and, arriving at the devil's palace, requite fight to the demons mounting baby-sit over their king, and after having defeated them, rush into the palace. At present Satan, seeing his life in peril, disappears in a cloud of fume and thunder, and is seen once more as he dashes through his vast domains gathering together his people, and while they wait the acquisition chariot another fight ensues. The devil is beaten again and the bottle of life is stolen past the leader of the victorious ground forces, and they are all nearly to depart when a terrible explosion takes place and the chariot and its occupants are dashed to the ground. All are killed but the brave woman who undertook the expedition, and she goes forth lonely… (p 463).

The synopsis — which was also printed in Views and Film Index on the same mean solar day– continues with explicit mention that "dragons and vampires" attempt "to stop her progress towards earth."

This seems to be the earliest mention in the American press of a moving motion-picture show featuring a supernatural vampire, the synopsis author presumably being someone working for Pathé Frères in the United States. But viewing the film, which survives, makes articulate why synopses published in other countries did not mention vampires. Nor did the same review published in Variety. The young lady's difficult journey back to the surface features characters that at start announced similar to dragons, but a careful test of the mise-en-scène—which includes sea-shells and marine plants—indicates they were likely intended to be sea creatures.

This case seems to exist the reverse of The Devil'south Castle, in that a period viewer (presuming the synopsis writer actually viewed the pic) mistook onscreen characters for vampires when no one else has, either at the time (so far as can be determined) or in the modern era. Yet, here the fault is potentially more complicated than what amounts to retrospective misreadings of The Devil's Castle. The viewer might well take establish Legend of a Ghost ambiguous (particularly insofar as not understanding scenes intended to exist underwater), and likewise found vampires to exist cryptic, not understanding what they looked like or how they should appear, whether in a picture show or otherwise, and thus disruptive the aforementioned with a ocean brute. The ambivalence of vampirism and early movie house had thus converged.

The Exploits of Elaine (1915)

I film that explicitly referred to supernatural vampirism during the early on cinema period was a movie serial. As Ben Singer (2001) explains, "sensational melodrama" was prominent in emergent feature films of the 1910s, only it was in "series films that the genre really flourished" (p 198). Even though the emphasis of early movie serials was on melodramatic action, their narrative content, chapter titles, and publicity at times drew upon horror themes, ranging from their imperiled heroines to their dastardly villains.

Episode 6 of the serial The Exploits of Elaine (Pathé, 1915) was titled The Vampire. In information technology, Elaine (Pearl White) shoots an underling of her nemesis, "The Clutching Mitt" (Sheldon Lewis). The only way to relieve his life is a blood transfusion. According to a plot synopsis published in Motography on February 14, 1915, the insidious villain:

thereupon sees an opportunity of killing two birds with i stone, that is, to save his tool's life and destroy that of Elaine. He sends two accomplices to Elaine's home, chloroforms her, and confines her inside a suit of armor which stands in the reception room of her ain domicile. The next morning an expressman is sent for this suit of armor, which has been damaged and orders repairing which [has] been given, and thus the helpless Elaine is boldly kidnapped in broad daylight, and taken to the Clutching Hand's abode. There her arm is bared, strapped to that of the wounded man, and the smashing doc prepares to perform the critical operation (p 243).

The police force rescue Elaine, halting the operation and saving her life, even as the underling "breathes his concluding almost immediately afterwards" (p 243). The Clutching Paw escapes from the government thanks to a sliding console in the wall.

On February 13, 1915, Flick Earth promised readers that the episode would brand viewers' "nerves creep at the uncanny ability of the terrible band and the claret boil at the audicity of the leader of it" (p 987). The episode was intended to affright audiences, at least in part. The trade added, "This is an unusual situation and nosotros suspect that no ane has e'er used it before—exist information technology remembered that no one sees all pictures" (p 987).

What exactly was the unusual state of affairs? Picture show World presumably meant a story in which the villain tries to force the heroine into giving blood to save some other villain. In other words, whatever initial excitement at reading the words "vampire and "blood" must exist tempered by a conscientious reading of the synopsis. In this case, "The Vampire" is the non-supernatural villain The Clutching Mitt. While a novelty in the cinema, the story had roots in nineteenth-century fiction.

In Hawley Smart's dime novel The Vampire; Or, Detective Brand's Greatest Case (1885), murder victims are found with two punctures on their neck. At commencement, it seems a vampire is on the loose, one "who leads an artificial life—who lives on the blood he extracts from his victims—that he sucks from their very veins, cartoon the red life-current straight from the heart." Only the solution to the mystery rationalizes the supernatural. As the murderer confesses, "My particular craze, when the fit came on, was to believe I was a vampire, one of those fabulous creatures who lives on homo claret. I slew my victims, and then I pricked them in the neck with the dagger point, merely as if the vampire'south teeth had bitten them." Just vampire's teeth had not bitten them, no more than The Clutching Hand took a bite out of Elaine. Equally Thomas Leitch has written in his written report of vampire adaptations:

… authorship is always collaborative because every author depends on the aid, example and provocation of innumerable predecessors and contemporaries, acknowledged or concealed, if only because every mode of communication by its nature involves the sharing of noesis (2011, p 11–12).

Knowingly or non, in other words, episode six of The Exploits of Elaine conjured earlier stories of the type Hawley Smart wrote, and by extension the fantastical literature of and then many other authors, ranging from Ann Radcliffe and Charles Brockden Brownish to Washington Irving and Edgar Allan Poe, in which the supernatural seems to be at play, but is not.

Vampire scholars have not discussed or analyzed The Vampire that menaced serial heroine Elaine. While period synopses conspicuously indicate its reference to supernatural vampirism, both in its chapter title and in its plotline, movie serials of the 1910s accept not been properly catalogued and remain under-researched. The episode title The Vampire languishes in relative obscurity, certainly to those investigating vampirism in the cinema, despite the fact that copies of it are archived at the George Eastman House, at the Museum of Modern Art, and at Library and Archives Canada.

The question remains every bit to how best to interpret and classify The Vampire. Its employ of supernatural vampirism every bit a metaphor is undeniable, but how distinctive or unique that was is quite debatable. After all, Burne-Jones and Kipling used vampirism as a metaphor also, as did all of the many aforementioned films featuring "vamps" (though some more than explicitly than others).

The Exploits of Elaine offers a unlike kind of a metaphor, but still only a metaphor, ane partially inspired past a body of works that, not unlike similar Hawley Smart's novel, had used the term "vampire" to draw sure kinds of thieves, criminals, and pirates. The most famous example would become Louis Feuillade's French picture show serial Les Vampires (1915-sixteen), which was distributed in the United States. All the same, prior to its American release were such films as Les Vampires de la côte/Vampires of the Coast (Pathé Frères, 1909), The Woods Vampires (Domino, 1914), Vampires of the Night (Greene Features, 1914), and Vasco, the Vampire (Imp, 1914): all of them depicted vampires as non-supernatural criminals and all of them were released in the Us. Much earlier, the play Invisible Prince! Or, the Isle of Tranquil Delights, staged in Boston in 1854, featured what one playbill called four "vampire robbers" named Ruffino, Desperado, Sanguino, and Stiletto.

To discover the title The Vampire is non then to observe a supernatural vampire in the movie theater, equally none appeared during its running fourth dimension. By contrast, The Vampire offers added insight into the ambiguities and multi-purpose usage of the terminology during the early cinema period. It also signals an important alert for those seeking supernatural vampires onscreen to continue with appropriate caution.

Loïe Fuller (1905)

Ten years earlier audiences saw The Exploits of Elaine, Pathé Frères released Loïe Fuller (1905) in the United States. The managing director is unknown, although it seems Segundo de Chomón was responsible for its hand-coloring. This French-made film showcased Loïe Fuller, the famous American artist who helped pioneer modern dance. Writing most Fuller's piece of work, Lynda Nead (2007) comments that "astronomy, illumination, cinematography, and the gendered allegorical body" had "come up together, finally, in the figure of Loïe Fuller" (p 241). She invented the serpentine dance in 1892 for a New York play about hypnotism, although it achieved its greatest fame soon thereafter at the Folies-Bergère in Paris (Fuller, 1913, p 25–40). Gunning (2003) describes her performances as "visual pyrotechnics created by colored and sharply focused electrical light and shadows using the swirling surface of Fuller's fabric as a screen for the projection of an equally protean succession of colors" (p 79). Far more than Max Schreck in Shadow of the Vampire, Fuller was both the project and the projected. The result was an ethereal, even otherworldy functioning.

In the film Loïe Fuller, a large bat flies onto the terrace of a country home or a castle, perhaps, as its outside is non depicted (Fig. 3). A clever transition occurs in which Fuller appears for a moment with the bat on her head (Fig. 4). When the bat disappears, Fuller spreads her costume in bat-fly style, her feet counterbalanced on the terrace ledge earlier she steps down (Fig. v). Fuller performs her trip the light fantastic toe, and so dematerializes cheers to a deliquesce, another cinematic sign of her potential supernaturalism.

Why might this character have been understood as a vampire when the graphic symbol in The Devil's Castle was not, fifty-fifty though both change from bat to human form? Cultural context provides the answer. For i, vampire dance acts became popular in the fin de siècle. According to an article published in the Charlotte News on October 29, 1890, an American minstrel visitor offered the "Great Vampire Transformation Dance" (p 4). Whether its transformation involved a bat is unknown, but it is clear that other vampire dances before long followed. In Massachusetts on February 12, 1896, the Springfield Republican reported that a "carnival of holidays" diverseness show included a "vampire" dance in which performers wore "black gowns with loose skirts, which were ornamented by gold stars and spangles (p 4). These dances apparently invoked the supernatural brute, given that they were staged prior to the creation of the Burne-Jones painting and the Kipling poem.

A frame from Segundo de Chomón's Loïe Fuller (Pathé Frères, 1905). The bat, plain a vampire bat, appears. As this work was published before 1923, information technology is in the public domain. This figure is covered by the Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

A frame from Segundo de Chomón'south Loïe Fuller (Pathé Frères, 1905). The bat appears on Loïe Fuller'due south head, every bit role of the transition. Every bit this work was published before 1923, it is in the public domain. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

A frame from Segundo de Chomón's Loïe Fuller (Pathé Frères, 1905). Loïe Fuller with bat wings extended, near the stop of the transition. As this work was published earlier 1923, it is in the public domain. This figure is covered by the Artistic Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License

Vampire dances became popular again in 1909, simply, by contrast, these afterward performances were additionally inspired by Burne-Jones, Kipling, and—mayhap virtually specifically—the stage play A Fool There Was. At to the lowest degree ii men took credit for their invention, 1 being Tom Terriss, whose dancer was Mildred Deverez. On December 4, 1909, the American Register and Anglo-Colonial World reproduced publicity for Deverez that referred to supernatural vampires as well equally those of Burne-Jones-style vamps (p 8). The other person who claimed to be the inventor was Joseph C. Smith. Co-ordinate to the Evening Waterloo Courier of April 23, 1910, his "weird" dance (performed by dancers similar Vera Michelena and Violet Dale) depicted vampire and victim in "symbolic postures" on a "darkened stage, with a blackness background, green spot lights and bars of red light coming from the depths under stage" (p 12). The male dancer wore blackness; the vampire wore a "greenish, serpent-like clinging gown" (p 12). This type of vampire dance appeared onscreen in Baronial Blom's Vampyrdanserinden/The Vampire Dancer (Nordisk, 1912), released in America by the International Feature Moving picture Co. The picture show—which is archived at the Det Danske Filminstitut—was salacious plenty to be banned in some U.S. cities. Its provocative dance features a man stumbling into a vamp'southward lair. She examines him with undisguised animalism. He is wary of her. Their movements are ho-hum and sexualized, the vamp first caressing and and then gripping his body. The dance culminates with the vamp strangling her partner, grin wickedly and even kissing him every bit she does.

More Americans would take seen The Vampire (Kalem, 1913). A synopsis in the Kalem Kalendar of October 1, 1913 notes, the lead character "goes to a theatre where Bert French and Alice Eis are presenting their famous 'Vampire Dance'" (p fifteen). According to company publicity, French and Eis played themselves in the film, having performed their dance onstage every bit early as the summer of 1909. On July 31 of that year, the New York Clipper described their performance every bit depicting the "adult female, youthful and voluptuous, tempting the man, and his terminal capitulation and decease" (p 637). The trip the light fantastic toe was, in other words, "taken from Kipling'south poem" (p 637). Footnote vii

How much the pre- and post-A Fool There Was vampire dances differed is difficult to determine. Descriptions of those staged during the 1890s are few, but they do suggest similar costumes and imagery appeared in nearly or all of these dances. By contrast, the reception of the dances might take changed, audiences in 1909 and in the immediate years thereafter agreement them equally not-supernatural given the ascendant influence of—and, at times, specific reference to—the Burne-Jones/Kipling creation.

In terms of the larger issue of vampire picture palace, information technology seems evident that, in the 1905 film, Loïe Fuller—who is in no way garbed as a devil or described as such in the title or in catalog synopses—was performing her own version of a vampire dance. Her bat transformation and dematerialization at the end of the flick suggests that she is not merely a female person vampire, simply a supernatural vampire, which at least some audiences in 1905 would likely take understood. Those watching the film in 1909 or in the immediate years that followed might well have read the film in a similar manner, but with the additional context of A Fool There Was and the afterward vampire dances.

How is information technology that scholars searching for early on examples of screen vampires have not recognized one in Loïe Fuller? The answer probably resides in its title, which simultaneously headlines a glory and yet obscures specific content. Rather than being a misreading of a film, here is a surviving flick that has not exist read in the modernistic menstruum, at least in the context of horror and vampirism.

Nevertheless, Loïe Fuller is quite mayhap the offset vampire film in cinema history. Information technology drew upon and deployed the supernatural character of earlier folklore and literature and stage dances, while simultaneously invoking the "vamp" tradition every bit well. The screen's inaugural vampire marked the convergence of various traditions, making information technology a especially complex entity: La danse macabre et la trip the light fantastic toe érotique. As Petr Malék has argued, "the vampire becomes a metaphor of intertextuality" (2010, p 129). Much the same could exist said of the intertextuality and intermediality that is primal to early cinema.

Conclusion

In Reading the Vampire, Ken Gelder (1994) provides the conception "I know there are no vampires … only I believe in them" (p 53). In Bram Stoker's novel Dracula, Van Helsing asks Dr. Seward to "believe in things that you cannot." The undead are not inscrutable, but they are difficult to comprehend and challenging to empathise, much in the same way that narratives in early moving pictures have occasionally seemed ambiguous and even elusive to viewers, not simply at the fourth dimension, simply also to the present solar day.

In terms of vampires onscreen, it seems credible that La légende du fantôme/Legend of a Ghost simply fooled ane viewer in 1908, only as Le manoir du diable/The Devil's Castle has fooled many viewers in recent decades. Neither features a vampire. To say they do constitutes misreadings of the two films. And nonetheless, to rephrase Van Helsing, audiences sometimes wish to believe in things they should non. After all, a number of critics have incorrectly taken the footage projected at the Cinématographe in Bram Stoker'south Dracula to be accurate imagery filmed during the early on cinema period, non simulacra created by Francis Ford Coppola, which it very definitely is (Cordell, 2013).

The first American-made picture to reference supernatural vampires explicitly might well accept been episode six of The Exploits of Elaine. At any charge per unit, the film was but one of many early on moving pictures that directly or indirectly used vampirism equally a metaphor. They began at least every bit early as 1908 withVampires of the Declension and continued through A Fool There Was (Play a joke on, 1915) and well beyond. Footnote 8 The Exploits of Elaine deserves recognition in a discussion of vampire cinema, but not necessarily more so than those inspired by Burne-Jones and Kipling. Indeed, The Vampire's metaphorical status arguably positions it nearer to the world of Burne-Jones than to Stoker.

To the extent that a supernatural vampire appeared in whatever picture show produced earlier 1915, it occurred in Loïe Fuller. In terms of its historical context and its narrative content, this seems to be an accurate reading. Loïe Fuller's title character possesses supernatural powers and very much appears to exist part of a vampire dance tradition that predates the metaphorical worlds of Burne-Jones and Kipling, rooted instead in supernatural sociology. That said, the intentionality of the filmmakers remains unknown. And no period responses to the film take survived, making commentary about how audiences in America or elsewhere received the film in 1905 at best informed speculation. As a outcome, the title grapheme of Loïe Fuller is difficult to fix, as if it is flickering with uncertainty betwixt the projector and projected, between "vamp" and "vampire."

Such ambiguities mark early movie house, to be sure, besides every bit all of moving-picture show history. Daniel Frampton rightly reminds united states of america, "Everything in a film may be well interpretable, simply not every formal moment has significant, arbitrariness is always possible" (2006, p 180). Vampires and films remain elusive in the years after the early movie house period, at to the lowest degree on occasion. Viewers would by and large agree that the character Ellen (Greta Shröder) collapses at the finish of Murnau's Nosferatu, but non all perceive that she has died, for instance. Fifty-fifty more than opaque are the oneiric and enigmatic worlds of Vampyr (Dreyer, 1932) and Nadja (Almereyda, 1994). The Kingdom of Shadows reigns to the present, with vampires amidst its longstanding residents.

The movie house is non actually vampiric, of class, permit lonely supernatural, but it is easy to see why Coppola and Merhige and others accept drawn the link between them. In Stoker'due south novel, Mina Harker records the devastation of Dracula in her diary: "the whole body crumbled into dust and passed from our sight." Written accounts of the vampire are all that remain, equally Jonathan Harker observes at the cease of the novel:

We were struck with the fact that, in all the mass of material of which the record is composed, there is inappreciably ane accurate certificate! Nothing but a mass of typewriting, except the later notation-books of Mina and Seward and and myself, and Van Helsing's memorandum. We could hardly ask anyone, even did we wish to, to accept these equally proofs of so wild a story.

Vampires are not ineffable, merely their codes of intelligibility are shifting and amorphous. Similar the cinema, vampires onscreen and off are shadowy, crepuscular, and nebulous, thus causing united states to project onto them.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicative to this commodity as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current written report.

Notes

-

In The Vampire Film: Undead Cinema (London: Wallflower Press, 2012) Jeffrey Weinstock notes that The Devil's Castle "has been described as the cinema'southward first vampire," but opts to refer to the character as a "devilish figure" (p 79).

-

Charles Musser, "The Travel Genre in 1903–1904: Moving Towards Fictional Narrative," in Early Movie house: Space, Frame, Narrative, edited by Thomas Elsaesser with Adam Barker (London: British Film Constitute, 1990), p 130.

-

Ibid, p 131.

-

An Excursion to the Moon is available on the 2007 DVD Saved from the Flames: 54 Rare and Restored Films, 1896–1944. Los Angeles: Flicker Alley.

-

A copy of Legend of a Ghost nether the championship The Black Pearl is available on the 2012 DVD Fairy Tales: Early on Colour Stencil Films from Pathé. London: British Film Institute.

-

Two years afterward, in The Dream Trip the light fantastic (1915), a man visits the Moulin Rouge and dreams a motion picture of a woman "comes to life and lures him into a wild vampire dance." Come across "The Dream Dance." June 19, 1915. Moving Picture World: 1986.

-

Other examples produced during the early cinema period include: The Vampire (Kalem, 1913), The Vampire of the Desert (1913), A Fool There Was (Lubin, 1914). The Vampire's Trail (Kalem, 1914), and Universal Ike, Jr., and the Vampire (Universal, 1914).

References

-

A Fool In that location Was. (1915). [flick] U.s.a.: Frank Powell.

-

Abbott Southward (2007) Celluloid vampires: life later decease in the mod globe. University of Texas Press, Austin

-

Batllori JMM (2009) Segundo de Chomón and the fascination for colour. Film Hist 21(1):94–101

-

Borton, T and D (2014) Before the movies: American magic-lantern entertainment and the nation's first green screen artist, Joseph Boggs Beale. John Libbey, New Barnet, Herts

-

Browning JE (2009) Introduction: documenting dracula and global identities in film, literature, and anime. in draculas, vampires, and other undead forms: essays on gender, race, and civilisation. Browning JE, Joan CE, (Kay) Picart (eds) Scarecrow, Lanham, Maryland, pp ix–22

-

Complete Catalogue of Lubin'due south Films (1903) Philadelphia: S. Lubin. A guide to motion picture catalogs by American producers and distributors, 1894–1908: A Microfilm Edition. 1985. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, Reel 3

-

Cordell SA (2013) Sexual practice, terror, and Bram Stoker's Dracula: Coppola'southward reinvention of movie history. Neo-Vic Stud 6(one):one–21

-

Edison Films, No. 94. (1900) Orangish, New Jersey: Edison Manufacturing Company, March 1900. A guide to motion film catalogs by American producers and distributors, 1894–1908: A Microfilm Edition. 1985. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, Reel 1

-

Elsaesser T (1990a) Afterword, In: Elsaesser T, Barker A (eds) Early Cinema: Infinite, Frame, Narrative. British Motion-picture show Institute, London, pp 403–413

-

Elsaesser T (1990b) Introduction, In: Elsaesser T, Barker A (eds) Early on Cinema: Infinite, Frame, Narrative. British Flick Institute, London, pp 11–30

-

Excursion dans la lune. (1908). [film] French republic: Segundo de Chomón.

-

Flynn JL (1992) Cinematic vampires: the living expressionless on film and television, from The Devil'south Castle (1896) to Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992). McFarland and Company, Jefferson, Due north Carolina

-

Frampton D (2006) Filmosophy. Wallflower, London

-

Fuller Fifty (1913) Fifteen years of a dancer's life, with some account of her distinguished friends. Minor, Maynard & Visitor, Boston

-

Gelder K (1994) Reading the vampire. Routledge, New York, NY

-

Gunning T (1990a) The movie house of attractions: early on film, its spectator and the avant-garde. In: Elsaesser T, Barker A (eds) Early Movie house: Space, Frame, Narrative. British Moving picture Found, London, pp 56–67

-

Gunning T (1990b) Archaic cinema: a frame-up? or the trick's on u.s.a.. In: Elsaesser T, Barker A (ed) Early Cinema: Infinite, Frame, Narrative. British Picture Constitute, London, pp 95–103

-

Gunning T (1991) D.W. Griffith and the origins of American narrative flick: the early on years at biograph. Academy of Illinois Press, Urbana

-

Gunning T (1993) 'Now You Run into It, Now You Don't': The temporality of the movie theatre of attractions. Velv Light Trap 32:3–12

-

Gunning T (2003) Loïe Fuller and the art of motion: trunk, light, electricity, and the origins of cinema. In: Allen R, Turvey 1000 (eds) Camera Obscura, Photographic camera Lucida: Essays in Accolade of Annette Michelson. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, pp 75–89

-

Harding C, Popple Due south (1996) In the kingdom of shadows: a companion to early movie theater. Cygnus Arts, London

-

L'homme dans la lune. (1899). [film] French republic: Georges Méliès.

-

L'arrivée d'united nations train en gare de La Ciotat. (1895). [film] France: Lumière.

-

La légende du fantôme. (1908). [flick] France: Segundo de Chomón.

-

Le Chevalier des Neiges. (1912). [film] France: Georges Méliès.

-

La défaite de Satan. (1910). [moving-picture show] France: Pathé Frères.

-

Le diable au couvent. (1900). [picture show] France: Georges Méliès.

-

Le fils du diable (1906). [film] France: Pathé Frères.

-

Leitch T (2011) Vampire Adaptation. Periodical of Accommodation in Moving picture & Performance four (1): 5–xvi

-

List of New Films, American and Imported, K-0002 (1900) New York: American Vitagraph. A Guide to movement picture catalogs by American producers and distributors, 1894–1908: A Microfilm Edition. 1985. New Brunswick: Rutgers Academy Press, Reel4

-

Le manoir du diable. (1896). [moving-picture show] French republic: Georges Méliès.

-

Le Voyage dans la lune. (1902). [film] French republic: Georges Méliès.

-

Les Vampires. (1915-16). [moving-picture show] France: Louis Feuillade.

-

Les Vampires de la côte. (1909). [film] France: Pathé Frères.

-

Loïe Fuller. (1905). [motion-picture show] France: Pathé Frères.

-

Lubin's Films (1908) Philadelphia: Southward. Lubin. A Guide to motion moving picture catalogs past American producers and distributors, 1894–1908: A Microfilm Edition. 1985. New Brunswick: Rutgers Academy Press, Reel three

-

Malék P (2010) Adaptation every bit 'Reading Confronting the Grain': Stoker'due south Dracula. Illuminace 22: 101–129

-

Melton JG (2011) The vampire book: the encyclopedia of the undead. Visible Ink, Canton, Michigan

-

Musser C (1990a) The emergence of cinema: the American screen to 1907. University of California, Berkeley

-

Musser C (1990b) The travel genre in 1903–1904: moving towards fictional narrative. In: Elsaesser T, Barker A (ed) Early on Cinema: Space, Frame, Narrative. British Moving-picture show Institute, London, pp 127–131

-

Nosferatu. (1922). [motion-picture show] Deutschland: F.Due west. Murnau.

-

Nead Fifty (2007) The haunted gallery: painting, photography, motion picture c. 1900. Yale University Press, New Oasis, Connecticut

-

Posner Bcurator (2005) Unseen cinema: early American advanced film, 1894–1941. Image Entertainment, Chatsworth, California, DVD boxed set

-

Prince Due south (2004) Introduction: The nighttime genre and its paradoxes. In: Prince S (ed) The horror film, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, pp i–eleven.

-

Satana, ovvero il dramma dell'umanità. (1912). [film] Italia: Ambrosio.

-

Shadow of the Vampire. (2000). [moving picture] USA: E. Elias Merhige.

-

Vocalizer B (2001) Melodrama and modernity: early sensational picture palace and its contexts. Columbia Academy Press, New York

-

Testa B (1992) Back and forth: early cinema and the advanced. Fine art Gallery of Toronto, Toronto

-

The Exploits of Elaine. (1915). [film] USA: Pathé.

-

The Forest Vampires. (1914). [film] USA: Domino.

-

The Gambler and the Devil. (1908). [pic] United states of america: Vitagraph.

-

The Ghost Train. (1901). [movie] The states: American Mutoscope and Biograph.

-

The Cracking Railroad train Robbery. (1903). [film] Usa: Edwin South. Porter.

-

The Vampire. (1910). [film] USA: Selig Polyscope.

-

Thompson K (1995) The limits of experimentation in Hollywood. In: Horak J-C (ed) Lovers of cinema: the first American film Avant-Garde, 1919–1945. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, pp 67–93

-

Vampires of the Night. (1914). [picture] USA: Greene Features.

-

Vasco, the Vampire. (1914). [picture] The states: George Hall.

-

Wright D (2001, reprint of 1914 edition) Vampires and vampirism. Lethe, Maple Shade, New Jersey

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Boosted data

Publisher'due south note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is licensed under a Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits utilise, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long every bit you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the commodity'south Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the cloth. If material is not included in the article's Artistic Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted employ, you will demand to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rhodes, G. The first vampire films in America. Palgrave Commun 3, 51 (2017). https://doi.org/x.1057/s41599-017-0043-y

-

Received:

-

Revised:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0043-y

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-017-0043-y

0 Response to "The Living Abstraction of Gothic Art the Vampire Film Undead Cinema"

Post a Comment